Irish Times Interview 2010

‘The dead don’t care and I don’t either’

Mon, Apr 05, 2010

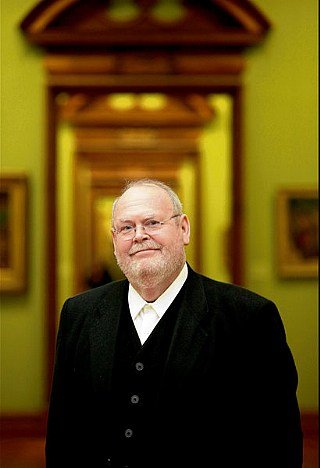

Thomas Lynch creates intimate character studies on the big themes of life – and death – but always with wisdom and sharp humour, writes SHANE HEGARTY

Thomas Lynch creates intimate character studies on the big themes of life – and death – but always with wisdom and sharp humour, writes SHANE HEGARTY

TO START with death is the ultimate cliche of any Thomas Lynch interview. The funeral director and writer has always been a journalist’s delight. It’s a challenge to find one that doesn’t introduce him almost immediately by that label, and this isn’t going to offer up a fresh option. So here goes, because Lynch is upfront with it – literally in the case of his first collection of fiction,Apparations Late Fictions , which begins with a short story about a man bringing his father’s ashes on one last and lasting expedition.

“You know I just never even thought of it,” he says over tea in the National Gallery. “Whenever I open a book of fiction, whenever I open a book of poems, whenever I go to the theatre, usually there are corpses involved and they’re not all undertakers involved in it. Maybe because they think I’m an undertaker and that’s my day job . . . but I see this book as being about fellow pilgrims who try and work their way through a world that includes mortality, d’you know? But it just never occurred to me that these were stories about death, even though most good theatre, most good narrative, most good poetry includes the notion of mortality. Somebody’s got to agree to stop breathing forever.”

Lynch is excellent company, as generous in his Michigan speech as he is in writing, constantly dealing in casual wisdom and sharp humour. His writing, then, is an almost seamless extension. Having established his reputation with poetry and, most notably, personal essays including The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade and Booking Passage: We Irish and Americans , his move into fiction has confirmed his ability to succeed across forms. It was, though, some time coming.

“I’ve always wanted to do fiction. I’ve always wanted to do everything. But fiction has always seemed to me to require more day-to-day attention, at least in my own mind it has, because managing that narrative is, to me, less a la carte work than poetry or essaying.

“If you’re a cafeteria essayist, it’s really good because you’re going from thing to thing and trying to find linkages, whereas once you get a character sort of fleshed out then they are going to do their thing and you need to follow the leads. So it needs to be day-to-day writing, at least for me. So I would take time and say ok I’m going to draft the story this week and work on it another week, but I would take days off in a row.”

His stories are intimate character studies that develop into meditations on the big themes – death, sex, religion. Of course, he says, “I’m borrowing that from every writer who has ever written. Romeo and Juliet is about nothing if not about sex, violence, death and mayhem.

“The book I wanted this book to be closer to is the Book of Job . This sort of comfortless notion that whoever is in charge here is really a double-dealing practical joker who’s making deals on the side. And yet Job keeps coming up with this default position that ‘God is good, blessed be the name of the Lord’. And I think people who can find some apparition, some glimpse of godliness in heartache and disaster and violence and the shit that happens, I think they are the people who probably end up being more grace filled and more faithful people than the people who naturally see God in the sunset and the new baby.”

Lynch describes himself as “devoutly lapsed”. “I’ve a great fondness for people whose life of faith includes the life of doubt. I’m named as a famous doubter. . .” He still spends most of his time in Michigan, but also spends a lot of time in Moveen, Co Clare, an ancestral home he has been visiting for four decades and which has featured heavily in his writing. His creative routine is simple. “I read and I write, that’s my day because, you know, I don’t golf. Reading and writing to me are pretty much the same thing. If I’m not writing something I’m probably reading something in preparation to write. But, I work early in the morning and I’m usually fresh until 3pm or 4pm in the afternoon and then I see whatever happens after that.”

He is working on longer fiction now, “and I have a character who’s up every morning with me and who’s behaving.” And he is still a funeral director, although he “comes and goes as he pleases” knowing that the family business has been passed on to the next generation. “I’m going for the hundred, and I often tell people that there’s a very slight discount if you make a hundred now, which is worth living for.

As for his own arrangements, “I think I’ve written repeatedly that the dead don’t care and I’m fairly convinced that I won’t care either. So, I don’t care. I’ve told them pretty much, play ball where it lies, you’ll know what to do, work away. But I think as a species that the best way to sort of get around all this is to just go through it. If you want to learn how to deal with life, find a living thing and deal with that. Find a baby or an old person who needs their diapers changed or their teeth flossed or a meal cooked. That’ll teach you about life more than sitting under a tree contemplating the great beyond. Do the great here and now and the rest will sort itself out.”

He chuckles. “The same with death: if you want to learn how to handle death, handle a corpse.”

Apparations Late Fictions by Thomas Lynch is published by WW Norton

© 2010 The Irish Times