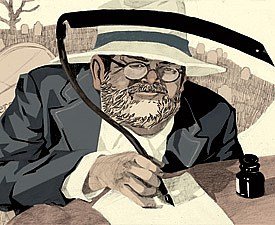

Thomas Lynch on Sex, Death, and Poetry

Utne Reader

from Willow Springs

It’s hard to imagine two more circuitous paths to renown than the vocations of writer and undertaker, yet Thomas Lynch has somehow staked a successful career on both routes. In fact, his workaday pursuits feed on each other. His experiences as a small-town funeral director in Michigan fuel books that circle around the theme of mortality, such as The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade (Norton, 1997) and the poetry collections Still Life in Milford (Norton, 1998) and Grimalkin and Other Poems (Cape Poetry, 1994). His prominence as an award-winning man of letters has in turn made him one of the more famous and oft-quoted undertakers in the land, a dash of celebrity in a sea of black suits.

Lynch is hardly wanting for media attention—he’s been featured on C-SPAN, NPR, MSNBC, you name it—yet he didn’t grab our attention until his elegant voice began appearing on the op-ed pages of the New York Times. Amid the tense bloat and blather of political pundits, here was a writer who was turning around big thoughts with gentle humor and rare reason.

We were attracted to this interview from the literary journal Willow Springs, conducted by Megan Cuilla, Mandy Iverson, and Aaron Weidert, because of Lynch’s sheer erudition on a number of broad matters. “I write sonnets and I embalm, and I’m happy to take questions on any subject in between those two,” he explains. —The Editors

On humor and death:

“I don’t set out to write anything jokey. But I do think that the way things organize themselves, the good laugh and the good cry are fairly close on that continuum. So the ridiculous and the sublime—they’re neighbors. If you’re playing in the end of the pool where really bad shit can happen, then really funny shit can happen, too.”

On sex and death:

“Yeats said to Olivia Shakespeare that the only subjects that should be compelling to a studious mind are sex and death. Those are the bookends. And think of it, what else do we think of, what else is there besides that?

“I think most people drive around all day being vexed by images of mortality and vitality. All they’re wondering about is how they’re going to die and who they’re going to sleep with, or variations on that theme—what job they’re going to have, whether they’re tall enough or skinny enough or short enough or smart enough or fast enough or make enough money, and all of it plays into these two bookends.

“If you’re writing about life, you’re writing about death. If you’re writing about life, you’re writing about love and grief and sex and all that stuff.”

On writing:

“I’m a writer, so I don’t wait for something interesting. I write. Period. And if there’s nothing interesting, I’ll make it interesting.

“For me, writing starts with a line, or some imagination, or some notion, and I just go with it as far as I can. You set yourself afloat on the language. And you think, I’ll see how far it can take me before this little raft I’ve cobbled together falls apart and everybody understands that I’m really just a fraud, or drowning—whichever comes first. But when it’s really working, readers go with you to the most unlikely places. They take big leaps with you.”

On writers engaging with the world:

“The reason poets aren’t read is that we don’t hang any of them anymore. We don’t take them seriously; we don’t think that poetry can move people to do passionate things. But poets did. Poets could change cultures. Before there was so much contest for people’s attention, poets were the ones who literally brought the news from one place to another, walking from town to town, which is how we got everything to be iambic and memorable and rhymed and metered, because the tradition was oral before it was literary.”

On the power of poetry:

“Poetry is as good an ax as a pillow. You should be able to cut with it if you want to. But I do want to avoid hurting people inadvertently. I don’t mind hurting people I intend to hurt—inadvertent damage is the thing I fear. I think all writers are capable of it. You’re dealing with powerful tools, you know; words are powerful business. I’m not saying you should be guided by fear, but I think general kindness is still a better thing. It’s just evolution. We want to be better people.”

On feminism:

“I was a single parent for a long time, which I think, for men, makes them feminists.

“One of the boxes you have to fill in on a death certificate is ‘Usual occupation,’ and for years, I would often have a son or daughter or a surviving husband say, ‘She was just a housewife.’ And I can remember thinking: You do it for a week and come back and tell me ‘just a.’ Because the effort to minimize the hardest work I’ve ever done was offensive. I can only imagine what it would mean to a woman who had done it all her life.

“All the women in my life have been powerful, powerful women with strong medicine—dangerous people. I just don’t see them in any way, shape, or form as having ever traded on victim status.”

On missing bodies:

“Part of my professional life has been marked by the disappearance of corpses in the funeral ceremony. Our culture is the first in a couple generations that attempts to have funerals with no bodies. We just disappear them. If you read the death notices in the paper today, you’ll notice that most of them are going to involve some type of memorial event, sans body, sans corpse. Also, most likely, without the gloomy stuff that comes along with having a corpse in the room. But the way to deal with mortality is by dealing with the mortals. And you deal with death, the big notion, by dealing with the dead thing.

“We’re very good when it comes to cats and dogs. We just don’t have a clue when it comes to our people. We have them disappeared without any rubric or witnesses or anything like that. And then we plan these ‘celebrations of life,’ the operative words du jour. These celebrations are notable for the fact that everybody’s welcome but the dead guy. This, to me, is offensive and I think perilous for our species. There is an intellectual—an artistic and moral—case that can be made for not only fruit and flowers in a bowl on a table, but also a dead body in a box.”

Excerpted from Willow Springs (Spring 2009), a literary journal that publishes fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and interviews and “engages its audience in an ongoing discussion of art, ideas, and what it means to be human”; http://willowsprings.ewu.edu.